East Haddam Gill Net Maker Transformed Fishing

Cofish made nets and foul-weather gear for fishers worldwide

Ed Stolarz with a line of Yankee Gill Net machines at Cofish in 1998.

In 1998, Ken Simon interviewed Edward Stolarz for the documentary, "Connecticut & the Sea." Stolarz owned Cofish International, an East Haddam fishnet manufacturer that was started in the late 1880s, remaining in its original location on Creamery Road through several ownership changes.

In 1938, the business was known as the East Haddam Fish Netting Business, owned by veteran netmaker John Brooks. Joseph Shea, who had worked for Brooks for about 25 years, bought the business in 1946 and renamed it Joseph F. Shea, Inc. Shea made several improvements to the company's Yankee Gill Net machines, an innovative technology that had been invented in East Haddam, and the business continued to flourish with worldwide demand for his netting. In 1950, Stolarz married Joseph and Mary Shea's daughter Virginia and started work at the netmaking company as a salesman. He acquired the business in the late 1960s, renaming it Cofish.

Cofish’s netmaking business finally succumbed to competition from Japanese netmakers in the late 1970s. Luckily, the company had diversified in the 1950s, when it started selling foul-weather gear to fishermen, allowing it to operate until Stolarz’s death in 2004, The rights to the Cofish line of gear were later sold to a North Carolina operator.

Ken Simon: What does Cofish stand for?

Ed Stolarz: That's an acronym for commercial fishing. The company was known previously as Joseph F. Shea, Inc. Before that it was John S. Brooks and we go all the way back to the Squire -- Mr. Squire, who invented the Yankee Gill Net Machine.

Q. How did this company get started in the net making business?

A. Wilbur Squire, as I understand, invented or began to invent the Yankee Gill Net machine in 1872 in the cow pasture across the street. And while he was developing the idea of the gill net machine, rather than the old Zang machines, he made the first machine out of wood to make sure it would work right. (ARTICLE CONTINUES AFTER IMAGE GALLERY)

And then he came across the street here in 1883 and put up this building for the sole purpose of manufacturing fish netting. We did not have electricity at that time. If you look at the building it's full of windows so that they could take advantage of daylight. And the machines were put up on the second floor so that they would be less affected by humidity and environmental conditions.

Q. What is a gill net?

A. A gill net is a net that is used to entangle a fish. As he tries to penetrate the net, the netting gets caught behind his gills and, therefore, the fish cannot go forward or backwards and because it's behind his gills and he can't close the gills, he drowns and that's the way they're harvested. But it's a very particular netting; we would make netting that was to within 1/64th of an inch to the proper size to catch a fish. So it was a very selective way of gathering fish and it wasn't and it wasn't very expensive.

Q. Before Mr. Squire invented a way to machine these nets, how were these nets made?

A. Back in the 1880's, 1890's, 1900's, there were several fish netting factories and many twine factories. And the reason we're talking about the Yankee gill netting machine is that the normal netting -- which were trap nets, purse seines and trawls -- the knots ran this way which were very, very bulky and with the Yankee gill net the knots ran this way so that they could get behind the gills much easier.

And the machines were not only very versatile, they were very fast. We could change a machine in less than one or two hours from one mesh size to another mesh size and depth and the machine could tie 3,000 knots per minute.

Q. How dominant were East Haddam and Moodus in the net making industry?

A. East Haddam was the cradle to the fish netting and twine industry. Most of the netting that was made in that period in the United States was made in this area. There was some netting made in Baltimore and some in Philadelphia but we were the big town -- Moodus and East Haddam.

Q. How important was this industry to the economy of the town?

A. Oh, it had a tremendous effect. Just from the point of this particular venture they employed about 25 people per year during the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s. When I took over we got up to 45 and 50 people. And most of our help would be classified as secondary help, housewives and women and so on and so forth. Most of them lived very close to the factory and, therefore, could take care of their family responsibilities as well as making extra money to supplement the family income.

As a matter of fact four of the houses within viewing of this building is where our people lived. Many of them -- of the 25 there were about 8 that never married -- so it was a sole means of support and there were two or three that had been widowed and it was not only a job for them but a way of life. They had a particular sense of dedication to their product and their fellow workers. We had no time clocks. We had very few people on piecework.

Each machine had a production tag stating the machine that the netting was made on, the operator of the machine and then a third place for the inspector of the netting, and this was all disciplined and even I signed the worksheets saying this is how much netting we're sending out and charge them for that, so there was discipline all the way through and there was a lot of pride in what we did.

Q. Was there a lot of competition in town among the net makers for business?

A. Not with us because most of them had moved in the middle or late 30’s to other areas and maybe even sooner.

Q. So you sold the nets internationally?

A. Yes, we did. Well, right after World War II we sold in Africa and it was interesting because it went over by freighter, then it went by railroad and then by ox cart.

There was such a demand in the revolutionary method of using nylon synthetic netting as compared to the old fashion organic materials because we could have one-third the size and therefore one-third the noise and three times the effectiveness and the nets never rotted.

So in effect, the reason we were able to have an international exposure and demand was because the knot to hold nylon netting in place was invented here and in East Hampton around 1948, '49, in that era. And instead of having to have three nets for a fisherman, now they could have one net. And the reason they had three nets is that they were hanging one to the lines, they were fishing one, and they were repairing the third.

Whereas with the nylon netting you didn't have to dry it or anything, you just put it overboard and fished it and it was much stronger than the others so we didn't have as much fatigue and deterioration. It revolutionized the fish netting industry.

Q. And you made nylon nets here?

A. Yes we did. Some of the first.

Q. So the machines were adaptable to nylon thread?

A. We had to change what we call a button. We had to put in an extra half knot to lock the nylon in place because nylon has a memory, it has a high coefficient of elasticity, 27 percent, and when you tied it into a knot eventually it would want to go back to a straight line. So that knot would blossom out and it would slip until we developed ways of overcoming that with the knot and with different chemicals that we used to shrink the knots.

Q. How did you sell these nets?

A. Well, actually, it was a combination of many things. You have to keep in mind that fish netting was a tool for the fisherman and therefore he wanted the best available at the best price. Now, in order to understand what he was getting, personalities became involved. Mr. Shea would travel on the road, Mr. Brooks would travel on the road. And I traveled on the road. And we sat with these fellows, we talked with them, we went fishing with them to understand how they use the nets and what we could do in our production techniques to make the netting better.

A. And we would have a few salesman but basically there was a lot of personal influence in the sale of the netting. And, of course, if they caught fish with your net they said they were good fishermen. If they didn't catch any fish with your net, they said they had a lousy piece of netting.

Q. Why did you close up shop?

A. The price of raw materials manufactured in the United States cost so much more money or as much money as the finished product that we were getting from the Far East and it was just a point of no return. I was working seven days a week and losing money at it. Saturdays and Sundays I'd come in here with my mechanic and we would repair or rebuild these machines because we couldn't afford to build new ones, and all parts were made right here. There was minimum overhead.

Now, the reasons the netting was cheaper from the Far East because it was being supported by their governments and the thing is not that they wanted to sell the netting, they wanted to be in control of food. So they would go around the world and get these orders for three times their capacity and as we came closer to delivery dates they would gladly go up 10 percent on their on their sales price. And then eventually when that was saturated, they just shut off the rest of the world. And the Asians did have the netting and they went out and caught the fish. So there was more to it than just fish netting.

Q. When did you stop making nets?

A. I turned off my machines April 1st, 1979.

Q. Were you the last net maker in town?

A. I was one of the last makers of gill netting in the United States. There was one, only one other left.

Q. So you got out of the net making business but you were still in the maritime industry.

A. Absolutely. As I mentioned earlier, the fishermen knew that we had good netting. Of course, if they caught fish they were the good fishermen, and if they didn't catch fish it was because the net wasn't any damn good!

I wanted to sell them something where they cannot deny the fact of quality, so I designed foul weather gear. Now, keep in mind in the 50’s before I would sell netting I would fish it in the Connecticut River like any other commercial fisherman and obviously I had to wear their gear, the foul weather gear and so on and I realized how important it was to have good foul weather gear – a good suit, good boots and good gloves is just as important as the net itself. And in working with it originally we had old black hard rubber, I mean, it hurt bad, it sweat and it just took the life out of you.

So when the PVC's first came out in 1957, I was one of the first to work with people from Norway. And Hellie Hanson gave me the East Coast distributorship for it because they felt it was a good thing for them and me.

In 1977, 1 began to design my own garments and had them manufactured with some people in Sweden and Portugal. For instance, the color orange was introduced by Cofish in 1977. We began to work with cotton backing materials, machine washable, forever life lasting.

The Valdez oil spill 10 years ago. We had been told that our gear lasted longer than anyone's. So I visited the major in charge of that Valdez and he said, “yes, the throwaway's didn't last a day, Hellie Hanson lasted five to seven days, but your gear -- they could do the 14-day tour, turn in their garments, we would steam clean them and give them to the next crew.” So quality has always been a factor. And a good understanding and respect for the customer was always there.

Q. Looking back on the days of Cofish and before that, the Squire Company, how would you characterize the heyday of this business and other businesses like it back in the late 19th Century?

A. It was really dependent on two things: trust of the customer and the supplier in that they got good netting and they got it on time when the fish were there and not according to production schedules. Like with the gill netting, I would go to Chesapeake Bay in June and talk to the netters and the seiners and find out what fish they were growing, what they had at that time, and then we would matriculate this into the biological growth for October, November and December fisheries and we would stock up on netting so that if we were right they had their netting overnight.

I had customers call me on Easter Sunday and said, “Ed, I tore up last night and I need some stuff in two or three days.” Guess what? He had it. So there is a tremendous amount of trust and cooperation. That is what made us in New England so important because they did pay attention. It was just a complete way of life and they were proud of what they were doing.

Q. Were there other things you tried at Cofish?

A. Yes, One of the things I investigated was the camouflage netting industry as our government knew it. And that was back in the late 50’s, early 60’s. 1 told them that they were 20 years behind time. They got upset with that number and they said they reviewed their requirements every six months but they said, “You come in and tell us where we're wrong.”

And we developed the beginning of the camouflage systems as they are now used in the free world. And it took me from 1961 to 1972 to do it along with Dow Chemical, Monsanto, Varian Associates. And what we did in that period, it was finally accepted in 1972 and there were no changes made in the free world camouflage nettings until 1985. That, I think was quite a valuable issue, improvement.

Q. You mentioned the parts were made here for these machines. Each of the mills had their own machine shop?

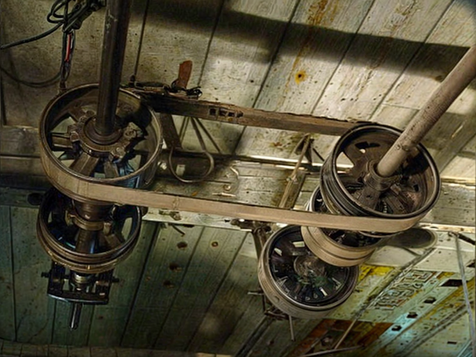

A. Indeed. We have two two motors here. One is a five-horsepower motor that runs all seven machines. The other was a 2-U2 horsepower motor that took care of our shaper, our miller, our lathe, our cutting machines, the drill press. We had four or five machines that were used to make the parts here. The castings were made someplace else but everything was machined and assembled right here.

To point that out even further, when I first married into the Shea family in 1950 we lived in a company house next door. Obviously, we didn't have air conditioning, so the windows were open in the building and I would sit down to the dining room table to have dinner and I'd say, “Virginia, I got to go because the Number Four machine's tension isn't right.” That's how dedicated we were to the machines.

Yeah. I could hear the machines and I could tell by the sound of the machine whether it was Number One, Three, Four or Five because of the loads that they were carrying. And once you heard that machine, you'd say, wait a minute, that tension isn't right, and you go over and reset the tension with the girl.

Q. You have these machines setup side-by-side, three in a row. Why is that?

A. The big reason is quality. When we would introduce a woman to a machine, it would take her three to five years to get the privilege of running a machine here. She would start out as a bobbin winder, then she would help fill the shuttles with the bobbins. She would learn how to mend the netting a little bit and then she would learn how to fill in the machine with another operator.

When she was ready to graduate to a fulltime machine operator she was put between the two machines and she'd run the middle machine and the experienced girls on each side of her would monitor her activities to make sure that the nettings were made properly, and it worked out quite well.

Q. So these machines were invented and patented here?

A. They were invented here but they were never patented because in order to get a patent there has to be full disclosure of technical procedures. We choose not to do that because nobody else in the world knew how we were doing it. As a matter of fact in the 1950's there were two or three delegations of Japanese that came here to see my father-in-law so that they could buy a machine from him or get patent rights and have him patent it and have them take it overseas. And he absolutely refused to let them come through that door where it said "Employees Only."

Q. Exactly what did these machines do that hadn't been done before?

A. They did two things. They were much more viable than other machines as far as changing mesh sizes and depths to make a new type of netting. We could do it in just a few hours where the other would take a day to do it sometimes because they have to take the whole gears apart.

We were able to change just one knob and change the mesh size and to change the depth it would take five minutes just cutting the threads back or adding some threads through the loops to make the depths different.

The first knob here is a tension adjuster. Just raise and lower it if you change the angle of attack of the twine coming down through and that is your first source of adjustment. If you look to the left and down you will see the springs and the hooks in there. Those silver hooks that are there, depending on the amount of twist we put on them -- one, two or three -- we, again add or decrease the resistance of the twine going through into the machine. And from those hooks then it goes to the springs which is your final point of tension.

And the fact that we could tie 3,000 knots per minute -- there was no other machine on Earth that could duplicate that. That's why I'm so proud to be able to stand here and be part of that history and hope that it can be propagated. We would like to see this a museum some day.

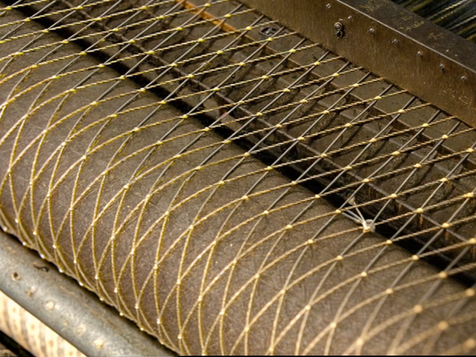

Q. What are we looking at here?

A. This is what we call a web of netting. This is probably around 20 meshes deep and because the roll is 150 meshes wide, we will have several webs. There's one, two, there's a hole there, three, maybe five webs. Now, it's not just the number of pieces of twine going through but it's the size of the mesh that determines the drag for tension as well. So it's a combination of the number of meshes you're making, the size of the mesh and the size of the twine that determine the amount of capacity per machine.

Q. How often did these machines break down?

A. Well, we had preventive maintenance all the time. Every two years each one of these machines was stripped to its frame and everything was replaced or rebuilt. So as far as breakdowns go, it usually came in the place of making adjustments on the hooks, the spring, the tension or the foot; we had a foot that twists the twine inside the machine and it makes the formation for the knot. Those were the wearing parts and they could wear out, oh, at any time whether it's a month, two months, three months, You couldn't predict it.

And the shuttles that are used in the machine, they would get like little whiskers on the edges and we would have to take sandpaper and file these down every two or three months at best.

Now, this here is what we call a rocker arm. That will either lift what we call the upper lock up, it'll lift up when the shuttles are in it and then it goes down when the loops have been made underneath the shuttles and then it comes down through a new loop, actually, and into the lower lock and released by these two screws right here. Those are release mechanisms for the locks.